Back Zwillingsparadoxon ALS مفارقة التوأم Arabic Парадокс блізнят Byelorussian Парадокс на близнаците Bulgarian Paradoks blizanaca BS Paradoxa dels bessons Catalan Paradox dvojčat Czech Йĕкĕрешсен парадоксĕ CV Tvillingeparadokset Danish Zwillingsparadoxon German

| General relativity |

|---|

|

| Special relativity |

|---|

|

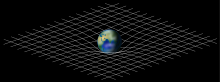

In physics, the twin paradox is a thought experiment in special relativity involving identical twins, one of whom makes a journey into space in a high-speed rocket and returns home to find that the twin who remained on Earth has aged more. This result appears puzzling because each twin sees the other twin as moving, and so, as a consequence of an incorrect[1][2] and naive[3][4] application of time dilation and the principle of relativity, each should paradoxically find the other to have aged less. However, this scenario can be resolved within the standard framework of special relativity: the travelling twin's trajectory involves two different inertial frames, one for the outbound journey and one for the inbound journey.[5] Another way of looking at it is to realize the travelling twin is undergoing acceleration, which makes them a non-inertial observer. In both views there is no symmetry between the spacetime paths of the twins. Therefore, the twin paradox is not actually a paradox in the sense of a logical contradiction. There is still debate as to the resolution of the twin paradox.[6]

Starting with Paul Langevin in 1911, there have been various explanations of this paradox. These explanations "can be grouped into those that focus on the effect of different standards of simultaneity in different frames, and those that designate the acceleration [experienced by the travelling twin] as the main reason".[7] Max von Laue argued in 1913 that since the traveling twin must be in two separate inertial frames, one on the way out and another on the way back, this frame switch is the reason for the aging difference.[8] Explanations put forth by Albert Einstein and Max Born invoked gravitational time dilation to explain the aging as a direct effect of acceleration.[9] However, it has been proven that neither general relativity,[10][11][12][13][14] nor even acceleration, are necessary to explain the effect, as the effect still applies if two astronauts pass each other at the turnaround point and synchronize their clocks at that point. The situation at the turnaround point can be thought of as where a pair of observers, one travelling away from the starting point and another travelling toward it, pass by each other, and where the clock reading of the first observer is transferred to that of the second one, both maintaining constant speed, with both trip times being added at the end of their journey.[15]

- ^ Crowell, Benjamin (2000). The Modern Revolution in Physics (illustrated ed.). Light and Matter. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-9704670-6-5. Extract of page 23

- ^ Serway, Raymond A.; Moses, Clement J.; Moyer, Curt A. (2004). Modern Physics (3rd ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-111-79437-8. Extract of page 21

- ^ D'Auria, Riccardo; Trigiante, Mario (2011). From Special Relativity to Feynman Diagrams: A Course of Theoretical Particle Physics for Beginners (illustrated ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. p. 541. ISBN 978-88-470-1504-3. Extract of page 541

- ^ Ohanian, Hans C.; Ruffini, Remo (2013). Gravitation and Spacetime (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-139-61954-7. Extract of page 176

- ^ Hawley, John F.; Holcomb, Katherine A. (2005). Foundations of Modern Cosmology (illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-19-853096-1. Extract of page 203

- ^ P. Mohazzabi, Q. Luo; J. of Applied Mathematics and Physics, 2021, 9, 2187-2192

- ^ Debs, Talal A.; Redhead, Michael L.G. (1996). "The twin "paradox" and the conventionality of simultaneity". American Journal of Physics. 64 (4): 384–392. Bibcode:1996AmJPh..64..384D. doi:10.1119/1.18252.

- ^ Miller, Arthur I. (1981). Albert Einstein's special theory of relativity. Emergence (1905) and early interpretation (1905–1911). Reading: Addison–Wesley. pp. 257–264. ISBN 0-201-04679-2.

- ^ Max Jammer (2006). Concepts of Simultaneity: From Antiquity to Einstein and Beyond. The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 165. ISBN 0-8018-8422-5.

- ^ Schutz, Bernard (2003). Gravity from the Ground Up: An Introductory Guide to Gravity and General Relativity (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-521-45506-0.Extract of page 207

- ^ Baez, John (1996). "Can Special Relativity Handle Acceleration?". Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- ^ "How does relativity theory resolve the Twin Paradox?". Scientific American.

- ^ David Halliday et al., The Fundamentals of Physics, John Wiley and Sons, 1997

- ^ Paul Davies About Time, Touchstone 1995, ppf 59.

- ^ John Simonetti. "Frequently Asked Questions About Special Relativity - The Twin Paradox". Virginia Tech Physics. Retrieved 25 May 2020.